Global Famine and Global Warming

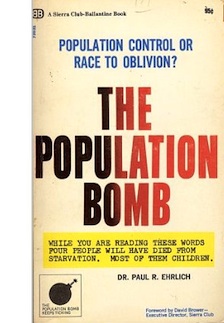

In 1968, the American scientist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, a best seller which was reprinted 22 times in its first three years. It began : “The battle to feed all of humanity is over…. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” The author warned of “famines of unbelievable proportions” occurring by 1975 and of “hundreds of millions of people” starving to death in the 1970s and 1980s. That same year, he wrote “Eco-Catastrophe!” in which he argued that the inevitable result of the imbalance between the birth-rate and death-rate would be the “greatest cataclysm in the history of man.” In 1970, he predicted that there would be water rationing in America by 1974 and food rationing by the end of the decade. “If I were a gambler, I would take even money that England will not exist in the year 2000.” he said.

Ehrlich proposed that the United States set up a Bureau of Population and Environment, which should favour financial rewards and penalties designed to discourage reproduction, such as taxes on cots, nappies, baby bottles and foods. He became a national celebrity. In 1970 he appeared 200 times on TV and radio programmes and gave 100 public lectures.

In 1972 there appeared the Club of Rome’s influential Report The Limits to Growth which supported Ehrlich’s claims. Using computer models, the Report predicted not only world food shortages but also that all the world’s oil would be exhausted by 1990. It was very beguiling ; the Report appeared in numerous languages and sold 30 million copies. I bought a copy, and found the arguments very persuasive. But none of Ehrlich’s predictions came true. In fact, the world’s known oil reserves were greater in 1990 than they had been in 1972, and today they are greater than in 1990, partly because more oil has been discovered, and advances in technology mean that far more can be extracted. At the time of writing (2013), large food surpluses are predicted for the next few years.

Ehrlich is now an advocate of climate change – not only that there is global warming, but that it is due to human activities, and will lead to a catastrophic rise in sea levels and other disasters. These predictions are based on computer modelling.

Tilo Ulbricht

Felix Dux commented:

Reading your piece led to me to revisit my copy of Limits to Growth: The 30 Year Update, published in 2004. As someone who earns his living from computer modelling, I may be biased, but I was impressed by the authors’ judicious use of computer models. I also think it is worth pointing out that, as far as I can see, the original (1972) book did not predict that the world’s oil would run out by 1990, although it did include a table which showed that the then known current reserves would be exhausted (which was broadly correct). They also argue that their original 1972 ‘model runs’ (they are careful not claim that these are predictions) have been largely borne out. None of these ‘model runs’ predicted any kind of global crisis until well after 2000. In most of their scenarios the crunch time occurs sometime during the middle decades of the 21st century. Most criticisms of Limits to Growth that I know of either concentrate on its tone (‘doom-laden’, ‘pessimistic’ etc.) or particular assumptions or predictions. But these criticisms don’t address the basic argument, which I would summarise like this:

If population and living standards keep on growing, then so will pollution and resource consumption.

If you rely on technical innovation and market forces to extract yet more resources and dispose of the resulting waste, then sooner or later you end up having to run faster and faster just to keep still. You also run the risk of not reacting to problems quickly enough.

These two factors combined mean that you eventually hit some kind of crisis, and growth goes into reverse.

The precise nature of the crisis, and exactly when it hits, depend on many factors and are hard to predict even with a computer, but it is possible to identify in broad terms the conditions which determine whether or not a crisis of some kind or other will eventually occur – and hence what things can be done to avert it. These come down, unsurprisingly, to coordinated, timely, global action to reduce population growth, per capita consumption, pollution, habitat destruction and so on. In 1972 the authors believed that there was still time for such action to be taken, but in The 30 Year Update the two surviving authors conclude that this opportunity may already have been missed.

There are ‘techno-optimists’ who claim that new technology will always come along quickly enough to get us out of trouble, but this is as close as anyone gets to a refutation of the basic argument. Maybe there is nevertheless something fundamentally wrong with the Club of Rome’s thesis – I certainly hope so – but I can’t see what it is.

I would say something similar about global warming. Computer simulations are used extensively by climatologists, but they are programmed using the scientists' theories about the physics and chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans. If it all turns out to be a big mistake – and what a pleasant surprise that would be – it will be because scientists have somehow missed a fundamental feature of how the climate works, not because they were too willing to believe what the simulations told them.